“Is the pig ready, Thaggard?” I asked.

The expert from Earth nodded. Then his face turned green.

The roughneck I’d assigned to babysit the guy shoved a sick bag in front of his face just in time. We all politely looked away as the groundhog emptied his stomach.

Normally, by the time someone reached Saturn orbit he was used to free fall. But the company wanted Thaggard and his ‘intelligent pig’ here fast, so he’d taken an express ship, boosting one-thousandth of a gee all the way. He’d never spent real time in free fall until he reached Titan Synch Station.

After a minute, Thaggard wiped his face and sealed the bag. “The pig is ready, Mr. Manjarres.”

“Thank you. Is the skyhook ready?”

That was a formality. The skyhook didn’t need to do anything. It just stretched ninety thousand kilometers between the surface of Titan and its anchoring rock. It supported the pipeline which was the reason for this project. But Beanstalk Incorporated had received a big share of Company stock as part of their compensation for building it, which gave them the right to send a representative for operations such as this. Humoring him was easier than making him shut up.

“We are ready,” said Jolicoeur.

“Launch crew ready?”

“Ready, boss,” said Bediskar. He was reporting in from the base of the skyhook, 72,000 km from us in the operations room.

“Pumps ready?”

Yang answered, “Yes.” He was also at the base.

“Launch the pig,” I ordered.

The big screen showed a feed of the launch. At the base, the pipeline attached to the skyhook split into five branches. One was an airlock for the ‘pig’ to be inserted. We’d watched the crew put the cylindrical machine in there earlier. The other four branches connected to reservoirs of hydrocarbons, waiting to be sent up the pipe.

Bediskar responded, “Blowing methane. Pig is moving. Pig is in main shaft. Closing valve.”

His part was done.

“Ethane pumping,” said Yang. “Valve open. Tracking pressure.”

Our attention moved to the monitor showing the pressure levels in the ethane branch. The heavier ethane, liquid at 150º Kelvin where methane was a gas, would push up the pig to send it through the pipeline. The pressure readouts matched the predictions. The pig was moving, floating on top of the stream of ethane pushing it up.

“We’re tracking the pig by sound,” said Yang. “On projected track.”

“Launch successful,” I announced. “Everyone begin monitoring shifts.”

We were looking at a few weeks before the pig joined us at Synch Station. It was moving slowly to start out. We suspected whatever was wrong with the pipeline was close to the Titan end. With luck, it had just accumulated some sludge on the walls that the pig would scrape off.

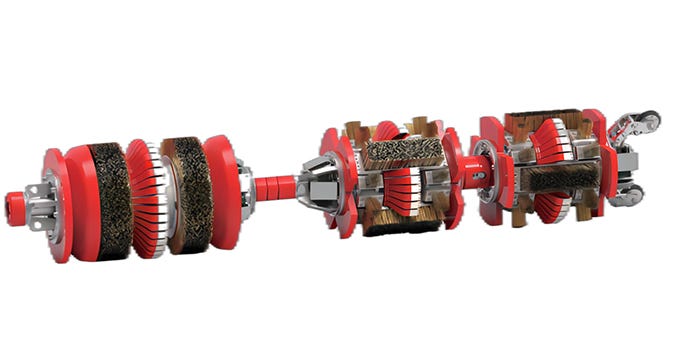

If there was a bigger problem than that . . . well, we’d gone for the ‘intelligent’ pig because it had an array of instruments to find problems. Clogs, cracks, corrosion, leaks—it was built to find them.

The men in the ops room relaxed. Except for Jolicoeur, who’d never been tense in the first place. One of the techs passed out bulbs of coffee. Thaggard declined one.

The groundhog was looking a bit better, though. He was finally learning to not jerk his head about. You could do that when you were used to free fall, but when you were still adapting, sharp head movements would set off the inner ear.

The babysitter gave Thaggard a bulb of water.

“Thanks, Czyzewski,” said Thaggard.

I’ll give him this, he’s polite.

I waited until Thaggard was done with his water, and I was sure it would stay down, before asking my question. “What does pig stand for? You never explained the acronym.”

The groundhog chuckled. “It’s not an acronym. It’s named for the animal.”

Czyzewski moved back from his charge. “You used to shove pigs through the pipes? That’s cruel.”

“No, not real pigs. We started with sponges. This was a few hundred years ago, so no one’s sure how the name started. The story I go with is that the sponges they ran through the pipelines squeaked like a pig squealing, so that’s how they got the name.”

“Huh.”

Thaggard shrugged. “It’s as good an explanation as any. And it beats having some hideous acronym we struggle how to pronounce.”

We’d called in Thaggard and his pig because the Titan pipeline was producing less than it had when it first went operational. Having a cheap source of hydrocarbons on this side of the Asteroid Belt was a boon to everyone who had nanoassemblers or food synthesizers. Ships lined up to take every liter which came up the pipeline to Synch Station.

The Company was thrilled. It promptly leveraged this new income source to support a massive expansion of facilities from Ceres to the Neptunian Trojans. All of the new income.

Which made the sudden drop in pipeline throughput five years into operation . . . concerning. Our weekly average was down twenty percent in the past year. The curve showed no sign of flattening. If it wasn’t fixed soon, the Company’s financial house of cards was going to come down.

Which was why the higher ups were happy to commission Thaggard to develop an intelligent pig customized for our pipeline and hire an express ship to bring them out here. If he can find the problem and we can fix it, that’s a modest expense compared to the revenue we’ll make from the increased hydrocarbon sales.

If it can’t be fixed . . . what’s one more debt for a bankrupt company?

For me, the station crew, and the roughnecks down on Titan, it was our jobs at stake. The Company has a lot of assets people would bid on at the bankruptcy auction. But if the pipeline is going to completely clog up, there’s nothing worth bidding on here.

Monitoring the pig’s trip was boring work. There was no way to track it. The Company looked at the price of instrumenting the length of the pipeline and said no. So we wouldn’t know what happened to the pig until it arrived and Thaggard downloaded its data. All we could do was monitor the pressure at the base of the pipeline. If it deviated from the projections, we knew the pig had found trouble.

The pipeline was full of methane gas which would compress as the pig went through the pipe. But starting out it would take over a day for a pressure wave to reach Synch Station, even if it wasn’t damped out. The base was the only useful access we had until the pig was more than halfway through the pipeline.

The column of ethane pushing up the pig behaved properly for three days. Then the pressure spiked. Yang’s crew halted the pumps. All the experts scrambled to their control rooms.

Thaggard studied the readouts. “Looks like it hit a clog, one too big for it to scrape through. Let’s do a ten percent pressure increase and see if that pushes the pig through.”

I checked with Yang that the increase wouldn’t exceed the strength of the pipeline, then authorized it. We had to wait a few hours to see the result. Speed of sound is a serious limitation in this kind of operation.

Finally the word came from the base. “Pressure increase! Time, two point six hours.”

After checking the numbers, Thaggard reported, “Looks like my pig is stuck about two thousand one hundred kilometers up the pipe.”

“Odd,” said Jolicoeur. “That’s outside the tangible atmosphere. There shouldn’t be anything affecting the pipe there.”

“What are our options?” I asked.

“Two choices. One, up the pressure to try to push it through. That risks breaking the pig. Two, withdraw some fluid to pull it back down.” Thaggard thought a moment. “I suppose we could draw it down, then up the pressure again and send it back at the blockage with some momentum. More chance of pushing through, but more chance of breaking it.”

“What do you recommend?”

“Two. Let’s bring it back and see what data we have.”

“I like data. Let’s do it.”

I sat back and listened as Thaggard coordinated with Yang’s crew to bring the pig down. It took hours to be sure it was moving. Lowering the ethane level in the pipe left the pig stuck at the blockage. The void between the ethane and the pig was filled with low-pressure vapor, getting lower pressure as the pumps took more ethane out of the pipe. That continued until the methane in the upper part of the pipe was pressing hard enough to pop the pig out of its spot.

Then it fell through the void and splashed back into the ethane, sending a new shockwave down for Yang’s crew to read.

At least, that’s the story they told me once all the data was analyzed. We wouldn’t know what really happened until Thaggard downloaded the data from the pig. The plan was for him to do that when it arrived at Synch Station, but that had gone the way of all plans.

“How soon do you want to go down to base?” I asked him.

“Now would be nice.”

Right. Titan’s one-seventh of Earth’s gravity wasn’t much, but it would keep him from throwing up. I arranged for the key personnel to take a shuttle flight down.

Czyzewski was one of the key personnel. Babysitting the groundhog in free fall was just minimizing how much of a mess he made. On the surface of Titan, a single mistake could mean death from hypothermia in minutes. The babysitter would have to track all of Thaggard’s gear and actions.

Jolicoeur wanted to come. I let him. He was as unqualified on surface operations as Thaggard, but if he died it was his employer’s problem, not mine.

The Surface Operations Center was where everyone supporting the skyhook and pipeline lived. It was ten kilometers from where the skyhook came down. The structural cables were embedded in a thick layer of water ice, which was rock hard at Titan’s temperatures. If it had been placed closer to the skyhook, the waste heat from the SOC would weaken the ice, possibly enough to let a cable tear loose.

Everyone traveled to the skyhook’s base in rolligons with well-insulated tires. They were still radiating heat from their coldsuits, but the wind blew enough cold air over them to keep the ice chilled.

By “air” I mean nitrogen and methane, with a bit of more complex hydrocarbons mixed in. Titan’s not one of those places you can take your helmet off for a moment. Especially if some liquid methane rain is coming down.

A shuttle ride put us at the SOC a day before the pig reached the surface. That gave us time to train Thaggard and Jolicoeur in using coldsuits. Czyzewski insisted on me going through it with them. I was annoyed. I have years of experience on Titan’s surface. Spending six months at Synch Station didn’t make me forget it all.

But I put up with the training. It let me provide a good example for the guy from Earth.

When the pig arrived, we were standing there in coldsuits. We looked like cartoon characters, all puffed up and swollen. But it wasn’t an empty balloon. We were surrounded by insulation, some of the best money could buy.

Bediskar picked up on the noise of the pig sliding down when it was three kilometers up. Yang slowed the pumps so it would handle the arrival gently. The crews worked the valves just right. We could hear it slide into the airlock of the launcher. The air is half again the density of Earth’s atmosphere, so sound carries well here.

The last of the ethane was drained out. The hatch opened. We could see the end of the pig. Thaggard reached out to grab it. Czyzewski slapped his glove and held the groundhog back. One of Bediskar’s men hooked it with an insulated rod and pulled it onto the track.

We all looked it over. It was an ugly gadget. The central cylinder was surrounded by several cones which pressed against the inside of the pipeline. More rods stuck out for the sensors—ultrasound, magnetometer, thermal, visual, a long list.

The gunk all over it didn’t improve its looks. The front end had chunks of brown stuff stuck to it. The rest looked like someone had poured motor oil over it. The rear was clean. The ethane must have rinsed it well.

“The electronics are fine,” reported Thaggard. “I’m downloading the data.”

“Good,” I said. We didn’t want to stay out in the wind any longer than we had to. A coldsuit used battery powered heaters to keep its occupant alive. The batteries would last for hours, but I didn’t want to put more wear on them than necessary.

It took most of an hour to do the download. I hustled my team back onto the rolligon. Bediskar’s roughnecks could handle cleaning and recharging the pig.

I secured a conference room in the SOC. Thaggard said he’d need hours to process the data, so I went off to take a nap.

Czyzewski woke me when the groundhog was ready to present his results.

They’d saved me a seat at the table. Good thing, the room was full of roughnecks wanting to know what was up with their pipeline. Every screen in the room had a graph on it.

Thaggard started talking when my butt hit the chair. “The good news is the inertial navigation unit confirms the position estimates we calculated from the pressure data were accurate within a couple of percent.”

That drew some pleased noises from Yang’s crew.

“Here’s the worst of the bad news: at two thousand and eighty-five kilometers altitude, the pig hit an obstruction about five centimeters high around the inner circumference of the pipe.”

That would explain our twenty percent throughput reduction right there.

“While the pig was stuck there, it did multiple measurements on the pipe wall. That portion of the wall is significantly colder than the lower levels. There’s also corrosion on the exterior of the pipe and cracking within it.”

The roughnecks responded to that with the vocabulary you’d expect.

Jolicoeur spoke over them. “That’s not possible. We built that skyhook with state of the art anticorrosion coatings.”

The man from Earth switched a graph to the big screen. “There’s the ultrasound reconstruction of the West-facing surface of the pipe at that altitude.”

It was easy enough to read. A ragged trench was dug into the outer surface. Several cracks were visible in the pipe wall. It scared the hell out of me. If that’s what we found on a first look, what was happening farther up the pipe?

“No, the anticorrosion coating would prevent anything like that,” insisted Jolicoeur. “We’ve been using those coatings on every skyhook we’ve built over Earth and Mars.”

Thaggard gave the Beanstalk Inc. man a hard look. “You put an antioxidant coating on the pipeline?”

“Yes, per the best practices clause in the construction contract.”

I felt the mood of the roughnecks change from worry to anger. None of them were professional chemists, but there were things you had to know to survive on Titan.

Czyzewski spoke first, prefacing his remark with an accusation about Jolicoeur’s personal practices. “Earth has monoatomic oxygen corroding objects in orbit. Titan doesn’t. We have monoatomic hydrogen, split off from the methane in the atmosphere. The pipeline needed an anti-reducing coating.”

I’m not sure if Jolicoeur understood that. His reply was, “I’d need to consult my technical staff on that.”

A roughneck snarled, “We need to—”

I cut him off with a bark of, “No contract violations.”

That made the lynch mob atmosphere subside a bit. But I hoped Jolicoeur wouldn’t say anything more stupid, or I might not be able to save him.

I needed to get the focus back on Thaggard, “What could you tell about the aerogel insulation layer?”

“Nothing,” he answered. “That’s too low density for any of my instruments to measure. But we must have lost it at this level, just by the temperature readings.”

“Okay. How can we get more data on the outer surface?” I asked that of the room generally.

Connor, the pilot of our shuttle, had taken a seat in the corner. “I could take some pictures of it.”

“Bullshit,” said one of the politer roughnecks. “You’d plume hell out of the skyhook.”

The pilot grinned. “Nah, it’s easy. I get on course for a fly-by of it. I cut the engine and go by ballistic. Snap my pictures. Then wait until I’m clear and light my engine again.”

“What resolution?” asked Thaggard.

“Oh, we have good cameras on our birds. We use them for surveying for heavy molecule deposits,” said Connor. “I’d need permission to do the flight.”

“Do it. Now,” I said.

“On it, boss,” he said as he left. The roughnecks all made room for him to reach the door.

My next demand was, “Who’s our best chemist?”

Yang pointed at one of the roughnecks. “Holubar.”

“Right. You start analyzing what monoatomic hydrogen does to steel. Have an answer by the time Connor gets back with those pictures.”

“Yes, boss,” said Holubar.

That gave me time for a meal. The SOC cafeteria serves good food. With unlimited amounts of almost every element for the food synthesizers, you could have just about anything you wanted. I went for meatloaf and gravy. Good comfort food for a stressful day.

Gossip spread the word of Connor’s return from his imaging mission, but I didn’t press for a word with him. The pilot had brought his pictures to Thaggard and Holubar. There was no point in bothering that team until they’d done their analysis.

Sometimes not micromanaging takes serious willpower.

Czyzewski fetched me from the cafeteria when they were ready. So many roughnecks followed me, I felt like I was leading a parade.

Thaggard did the talking again. He put a picture covering about a hundred meters of the skyhook on the big screen. “The center of the corrosion area is this visible line, but there’s lesser amounts of corrosion detectable up and down the pipe from there. One piece of good news. The skyhook cable isn’t affected by corrosion as far as we can tell.”

I’d expected that. Braided carbon nanotubes didn’t have much vulnerability to hydrogen.

“Looking from the least to most corroded areas, the pattern seems to be this. The aerogel insulation coating is penetrated. That exposes the steel of the pipe to the hydrogen. There seems to be two mechanics at play.”

Thaggard switched the image to the corroded trench diagram. “Hydrogen radicals hit the steel and bond with the carbon atoms. For the non-chemists, mixing iron with a specific amount of carbon makes steel. So if the carbon is turned into methane molecules—or more likely just methylene, not fully hydrogenated but still with enough iron bonds broken to pop it out of the metal—the steel becomes wrought iron. Which isn’t jello, it’s strong stuff, but the properties are different enough it flakes off the pipe. Takes some more of the aerogel with it, so there’s less insulation, more exposure to hydrogen.”

New image: a pipe cross-section with cracks marked on it. Lots of cracks. “Hydrogen which doesn’t bond with the carbons penetrates farther into the steel. That gives us ‘hydrogen embrittlement,’ a known phenomenon. As the pipe flexes over each revolution of Titan, the cracks separate and spread.”

Titan’s orbit is a little eccentric, so ‘pointing straight at Saturn’ and ‘straight up at the anchor point’ don’t always match. The skyhook has enough flexibility to handle the sway needed. So does the pipeline—when it’s an intact tube of steel.

“At this altitude, cracks all the way through the pipe wall will intermittently open to space, so we wind up with vacuum freezing of the pipeline contents. That’s what created the blockage that stopped the pig.”

“Hold on,” I interrupted. “You’re saying the pipe is broken clean through? Why didn’t it fall down?”

“The pipe is held to the skyhook cable. That’s what’s holding it in place. The pipe doesn’t need to hold itself up, it just holds the fluids in.” Thaggard put up an image of the pipeline design, with loops of carbon nanotube braids holding each segment of pipe to the skyhook cable.

“Okay, so we don’t need to worry about pieces falling off until the cracks spread enough to separate a chunk of the pipe.”

“That shouldn’t happen for at least another year or two,” said Thaggard.

I’m pretty sure he meant that as reassuring. I wasn’t reassured. “Okay, we have a diagnosis. How do we make with fixing it?”

Thaggard gave up his spot up front to Holubar. That reassured me. If a roughneck thinks he can fix something, it usually gets fixed.

Holubar began, “We can do a short term fix. Long term is going to take developing an anti-reducing coating and applying it to all the affected parts of the pipe. Might have to replace some segments, too. That’s going to have to go to R&D.”

He put up a diagram of the pipe. “What we can do now is a patch job. Cover the worst corroded areas with sheet metal to seal the cracks. Then put on a protective layer that will absorb or deflect the hydrogen. We can’t make aerogel here. We’re thinking woven nanotubes, if our assemblers can support that.”

That provoked some discussion on our supplies. I stayed out of it, the boys knew what they had and what they could make.

To my surprise, the steel was easiest to get. The anchor rock for the skyhook was Polydeuces. It had been a Trojan moon of Dione, one of the inner moons of Saturn. Shifting it to match Titan’s orbit had been a production, probably the most expensive part of building the skyhook. Astronomers were still mad about it.

Polydeuces had a chunk of nickel-iron in it, probably from some asteroid caught up during its formation. We’d used about half of it creating the pipeline. The forge was still there. We’d send some roughnecks up and they’d create the rolls of sheet metal we needed.

Producing blankets of carbon nanotubes would be harder. A groan went through the room when Yang suggested reprogramming the food synthesizers to make some. That would let us get the job done in two weeks.

Two weeks of everyone eating emergency rations.

Yang’s response, “What’s worse, e-rats or losing your jobs?” shut down the objections. But it didn’t make anyone more cheerful.

“How are we going to install this stuff?” asked Bediskar. “Construction bots?”

We all looked at Jolicoeur. He looked unhappy. “The bots were sold off when construction finished. They went to Ceres. I think they were resold since.”

“Okay, it’s going to be a job for roughnecks,” said Holubar. “We can handle it. What’s the best way to get there?”

“It’d be easy to get there if the Company had paid for the elevators,” griped Jolicoeur.

We ignored him. Elevators which could stay attached to the skyhook in Titan’s over a hundred meter per second winds cost more than anyone could afford.

Czyzewski grinned. “We rappel down. We might set a record. It’ll be easy in the free-fall portion.”

Yang glared at him. “Do you have a seventy thousand kilometer rope in your locker?”

Someone else suggested climbing up from the base. Even at one seventh gee, going two thousand kilometers straight up wasn’t a practical climb.

Connor said, “I can deliver you there.” He laughed at the looks he received. “It’s not hard. I go ballistic on a collision course with the skyhook. Kick the work crew out. Use the maneuvering thrusters to dodge the skyhook. The crew uses their maneuvering packs to soft-land on the pipe. Easy.”

“And how do they get back down?” I asked.

“Parachutes. Easy.”

It wasn’t that easy, but when we ran the numbers, it could work. It was dangerous though. I told everybody to get started on making the patch materials while I sent a memo to Company headquarters.

I told them what we’d found, how we wanted to fix it, and requested permission to do the fix. I make a habit of always running decisions that can get men killed upstairs. That way they have to pay out the survivor benefits.

The answer came back faster than I expected. Approved. With a bonus of six month’s pay for everyone who went on the repair mission.

The Company really wanted the pipeline to start flowing again. They must be twitchy as heck over it being shut down for the pig runs.

I shook them down for a smaller bonus for everyone on the planet, to make up for the food synthesizers being repurposed. Then it was just waiting for everything to be ready.

The steel rolls were ready first. Connor flew them down from Polydeuces.

Lots of roughnecks volunteered for the repair crew. Checking for welding and free fall experience filtered out most. I settled on Bediskar, Czyzewski, and Jenkins, one of Bediskar’s crew, to come with me.

Czyzewski asked, “Boss, when’s the last time you did welding in vacuum?”

I glared at him. “Two months ago. Fixing one of the benzene pipes on Synch Station.”

“Okay, okay, sorry.”

“I don’t spend all my time behind a desk.” Too much time, which is why I wanted to be on the fix crew.

I also didn’t want to be sitting safely at a desk if one of them got killed on the job. This could be rough.

The last thing ready was the ‘sled.’ It was an open framework holding the rolls of steel and nanoweave. Several rocket thrusters would maneuver it to a gentle docking with the pipe. Then electromagnets would hold it there.

We’d considered carrying the rolls ourselves, but with the maneuvering packs, welding gear, parachutes, and other stuff we had to wear on our space suits, there just wasn’t room.

Yang organized a send off for us. He produced a whiskey bottle and led a toast for Connor and the fix crew before we launched. We couldn’t have any, of course. No alcohol before outside operations. Felt like he was rubbing it in.

Connor gave us a gentle flight. We flew out of the atmosphere, coasted for about ten minutes, then the external doors opened. Connor transmitted, “Corrosion Station, all out!”

I pressed the button to send the sled ahead of us, then led my team out the door.

The shuttle slid smoothly away from us. Connor was good, he didn’t plume anybody.

We started our thruster packs to decelerate us toward the touchdown. We angled apart from each other to make sure we wouldn’t collide on landing.

The radio channel was quiet. This was a little too serious for anyone to crack jokes. The support team was listening in from below, ready to share any info we needed.

The pipeline grew from a near invisible line to something with actual thickness. I checked my suit radar. Right on track.

“Oh, shit.” It was Czyzewski. “I’m off course. I made a bad input. I’m going to miss.” He went into a stream of cursing.

“Relax,” I ordered. “You’ve got your parachute. Search and Rescue will find you. Just stay calm and do the reentry procedure.”

“Right. Right.” He started cursing again, then cut off in the middle of a word. Must’ve muted himself.

“This is SOC operations,” said Yang. “We are tracking Czyzewski’s beacon and prepping a hopper for recovery operations.”

The pipeline appeared. My thrusters fired. I slapped against it with a ringing thump. The electromagnets in my kneepads and hands activated. Three of the four made a good grip. I was attached.

Looking up I saw the sled firmly attached. Below me I could see Bediskar and Jenkins silhouetted against Titan’s disk. Czyzewski was already out of sight.

I was worried about him. The plan was to launch weather balloons when we were ready to come down, so Search and Rescue could predict where Titan’s fierce winds would drop us. The hopper would meet us on the ground before the cryogenic climate could suck all the heat out of our space suits. Instead the hopper would be chasing Czyzewski. I hoped they caught him in time.

“Hopper launched,” said Yang.

We pulled a roll of steel from the sled. Unrolling it gave us fifty meters by almost a meter of metal. Four of these would let us cover the worst of the corrosion and put a seal over the pipe. It wouldn’t be completely airtight, but if we could hold in most of the vapor we wouldn’t have vacuum freezing any more.

One edge was tucked into where the skyhook cable met the pipeline. Jenkins went along the sheet, marking where the loops held the pipe to the cable. The last thing we wanted was to cut one of them with our welding torches.

“We have beacon. He’s moving at high speed in the upper winds.”

With only three of us it took longer to finish the welds than planned. But the next strip went into place. We welded it down. Some vacctape covered the gaps over the loops. It would only last a few months before peeling off, but hopefully we’d have a start on the permanent solution by then.

The last strip of steel was tucked into the cable join on the other side. It was just a bit wider than it needed to be. Our fists were sufficient to hammer it flat so we could weld it onto the previous strip. That was the hard part done.

Yang reported, “Czyzewski is in the lower atmosphere. Hopper is headed for him.”

Holubar synthesized some glue for us to attach the nanoweave mats to the pipeline. We scraped away the remaining aerogel so we could get a good connection to the steel. Once the edge of the mat was attached, we started it unrolling.

It behaved like cloth. Better. A hundred meter bolt of cloth wouldn’t have unrolled that smoothly. We needed to follow it along and tuck it under the skyhook cable. Once that was done, we just needed to pull it tight and glue down the bottom end.

“Lost his beacon at touchdown. Hopper heading for last location.”

That probably meant Czyzewski had gone into a methane lake. Not good. The cryogenic liquid would suck the heat from his suit by conduction, much faster than the air would.

The second and third nanoweave mats were easier. We just let them unroll and pulled them straight. A bit of glue and we were done.

“Hopper sees a steam plume, going for pick up.”

That meant he was in a lake, and the liquid methane was boiling around him.

The fourth mat had to be tucked against the other side of the cable. Fiddly work. I was glad we had to do it. It kept us distracted from listening to updates on the radio.

A transmission came from the hopper pilot. “See him. Grabbing him.”

A moment later there was one more word. “Alive.”

Jenkins pressed his helmet to mine. “You’d think they could say a little more about him.”

“They’re probably working like hell to keep him alive.”

Once pulled tight, we glued down the end of the last mat. The glue left over we used to seal the mats to each other until we ran out.

The radio sounded again. The hopper pilot. “Okay, he’s stable. Gonna have to send him to Ceres to have his fingers and feet regrown, but he’ll keep everything else. Returning to SOC.”

I hung from my magnets. I wouldn’t have to write a letter to Czyzewski’s wife. Okay, I should write her a letter, but it wouldn’t be the hardest kind.

“That’s all the glue, boss,” said Bediskar.

“Right.” I turned on the ops channel. “This is the repair crew. We’re ready to come down.”

“Acknowledged,” said Yang. “We’re releasing the weather balloons now. Give us half an hour for them to reach altitude and we’ll be ready for you to jump.”

“Will do.”

Nothing left to do but play tourist. We couldn’t watch Saturn’s rings. They were edge on to us here. I stared down at Titan.

From Synch Station it was just an orange blur. But here we were close enough to see the patterns in the clouds. They moved as I watched. Huge clouds made puffballs toward the poles. The time flew by.

“Hopper Two is set to go. Ready for you to jump,” said Yang. “Please jump from East side. Space at ten second intervals.”

“Will do.” I turned to the other two. “Youngest first.”

“Not arguing,” said Jenkins. He leapt off the pipeline.

Bediskar counted ten then jumped. I followed at the proper time.

Skydiving over Titan gave an even better view of the clouds. I felt the atmosphere pushing at me before I reached them. We jettisoned the maneuvering packs then, keeping them clear of the skyhook.

We couldn’t open the parachutes too early. There had to be enough air to fill the canopy, or it might fold in on itself and be useless. Yang gave us the signal.

Drifting down on the parachute was fun until we reached the wind belt. Then we were going sideways, being yanked too hard to enjoy the view.

“We have your beacons. You’re tracking to the estimate we had from the balloons,” said Yang.

I was glad I hadn’t eaten the snack paste in my space suit helmet, despite feeling a little hungry. I was regretting the water I’d had. The wind was flinging me about so much I wanted to hurl.

Bad idea in a space suit.

We were in the thick haze now. All I could see was orange. No shapes visible. This was the smog hiding Titan’s surface.

Finally we dropped down to where the air was clear. I was already feeling cold. Some dunes stretched out below us, wavy lines of ethane sands.

“Hopper Two here. We see your chutes.”

I twisted around. I could see one parachute below me. Not the other. It wasn’t much farther down, but had to be at least three kilometers away.

I lost sight of it as I came in for my landing. It wasn’t as bad as I feared. The light gravity let me hit without breaking anything. Still wound up on my butt.

The sand chilled my butt and legs as I sat there. I released the straps of the parachute and stood up, turning to see what was around me.

Some boring dunes and the hopper coming to get me.

In a moment I’d been pulled through the door and wrapped in an electric blanket. The chill started to fade. A medic interrogated me for injuries and numbness.

“I’m fine, really. I was a little cold but that’s fading. How’s everyone else?”

The medic jerked a thumb at my fellow repairmen. “They’re fine. Czyzewski is being packaged to go on the next ship to come to Saturn. Should be awake in a few hours.”

“Thanks.”

The hopper was already taking us back to SOC.

We were greeted with cheers in the cafeteria. This time we did drink some of Yang’s whiskey. I delegated authority for pig operations to him, so the pig could be launched again without waiting for me to sober up.

Thaggard had modified the pig to scrape at obstacles when stuck, so it went up the pipeline without delay. The whole run took twenty days. The speeds involved made Thaggard twitch, but you can get away with moving at a quarter of the speed of sound when your pipe is perfectly straight.

We went up to Synch Station four days before the pig arrived. That gave the expert from Earth a bit more time to adjust to free fall before having to work on the pig.

I assigned him a new babysitter.

The pig arrived looking dirtier than it had the first time. But the pipe should be cleaner, which is what we wanted.

Thaggard spent most of a day reviewing the pig’s data before announcing we were clear for resuming operations at full throughput. There wasn’t any whiskey on Synch Station, but we celebrated with some locally made vodka.

The babysitter let the Earther drink too much. I don’t envy him his first free fall hangover.

More stories by Karl K. Gallagher are on Amazon and Audible.

Great work. I keep expecting things to end a lot more poorly for the characters, and I’m relieved when they survive

This story has so much going for it! I especially liked the narrator’s outlook. The engineering all felt real, too.