Leak

Small problems, left unfixed, become big problems. You don't want small problems in a space station.

Linda jerked awake as her alarm sounded. The movement started their sleep sack oscillating in the near-zero gravity.

Her husband Tony moaned, “Oh, God, not this again.”

“You can go back to sleep,” she said as she slid out of the sack. She opened the hatch to their apartment’s living room.

“No, I can’t, not with you bouncing around the place.” He followed her through the hatch, closing it to preserve the air seal. He glanced at the monitor on the adjoining hatch. Their three year son, Andy, was still asleep.

Linda kicked off the bulkhead, sending herself straight to the sink on the north side of the room. She had her comm out, snapping pictures of it. Her prediction was right. It was time.

A globe of water hung from the faucet. It was about the size and shape of a cantaloupe, attached to the tip of the spout at one end. The breeze of her passage shook it, sending waves over the surface. When she landed on the kitchen unit, the vibration broke the last surface tension holding the globe to the spout.

It started to drift away, toward the south side of the room.

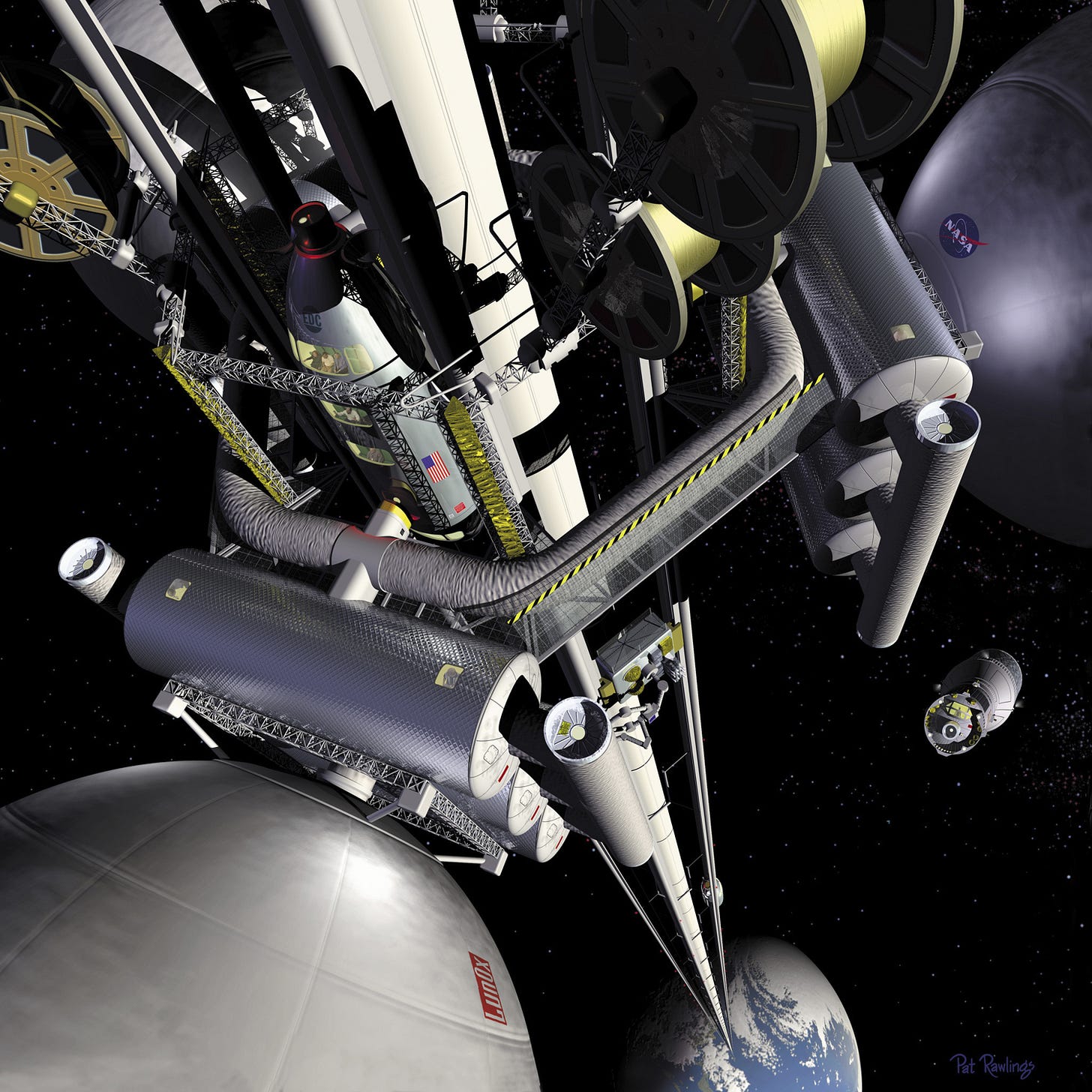

Artsutanov Station hung at the geostationary level of the Ecuador space elevator. Over the decades the station kept growing. It was flat in design. Anything added at a higher or lower altitude would be pulled away from the station by tidal forces. It could expand east and west with no added stress, the new construction staying in the same orbit as the core. Building to the north and south resulted in compression forces as the material tried to follow its natural orbit to the equator.

Linda and Tony’s apartment was in the newest northward expansion, ten kilometers from the center of the station. It still felt like free fall. But anything left unsecured would wind up on the south side of the apartment in minutes. Quarter of an hour at most.

She kept snapping pictures of the water globe as it drifted across the living room. One every half minute or so. Tony kept his grumbling barely audible, so she ignored it.

The bucket provided by Maintenance sat on the south wall, held in place by some StayPutty. The water was moving nearly a thumb-width a second as it entered the bucket, more than ten minutes after it had been set free.

Linda slapped the lid on the bucket before it could splash back out.

“Are we done?” asked Tony.

“Let me clean up.” She picked up the bucket and bounced back across the living room to the sink again. The sink’s drain was a flexible suction hose. She waved the hose through the water sloshing about the bucket, sucking all the water away.

“You could have done that ten minutes ago. Or before we went to bed, even.” Tony was always cranky when he didn’t have enough sleep.

“I know. But then Maintenance would say it was a solved problem and close the ticket. I want this fixed.”

“It’s a leaky faucet, Linda!” He was whining now.

“It’s a leaky faucet now. Who knows what it’ll be if the problem is left to grow. We live and work on flimsy, complex machines. In space! I don’t need to justify my hatred of willful incompetence.”

He sighed, then opened the hatch to their bedroom and went in. Linda followed. Maybe a footrub would help Tony fall asleep faster.

Tony went cheerfully off to work after three more hours of sleep and a good breakfast. Andy was still asleep, so Linda seized the chance to update her maintenance ticket. She selected the five best pictures. They illustrated her commentary on the problem, ending with, “Splashing water could cause electrical shorts or damage other equipment, as the bucket does not contain it.”

She stabbed the ‘send’ button with satisfaction. Now they’d have to accept it was a real problem.

Once Andy was awake, she fed and washed him efficiently. They’d been on Artsutanov Station for over a year, so the child was finally willing to eat food instead of seeing how far he could fling it in free fall. It helped that she’d made connections with the residents-only hydroponics gardeners for the good food.

The hand-me-downs from Andy’s cousin still fit. Fortunately, toddler clothes worked well in free fall. Most of Linda’s wardrobe was still in storage Earthside. Sundresses did not work in space.

Linda led him to the park. Andy bounced from side to side in the corridor, burning up extra energy. She was finally learning her way around the maze of the station. The murals in the corridors weren’t just decorations, they were landmarks. She’d have to do one for her own corridor. The new parts of the station were still bare metal.

Gibson Park was reserved for Jacks—the permanent residents of the station. No tourists were allowed. Linda was accepted now. New residents often didn’t make it through their first year. With all the stresses of free fall, vacuum hazards, claustrophobic quarters, and hazing from the crankier Jacks, people were as likely to drop back to Earth as settle in for the long term.

One of the other moms, Tomasina, greeted Linda with a smile. Her daughter was a four year old named Alice.

Alice promptly seized Andy’s hand. “It’s time to pick leaves!”

The children floated toward the quartz window letting filtered sunlight into the park. The volume was filled with poles and jungle gym frames for the children to play on. Ivy, kudzu, and other creeping plants swarmed along the length of them.

The plants would cover the window if they were allowed. Pruning them back to the edge of its frame was the duty of the children. Linda wondered if it was intended to be an outlet for destructive urges or just an excuse for Maintenance to be lazy again.

Andy and Alice quickly filled their bag with leaves, then zipped through the bars to the compost bin before heading back to do more.

“I’m glad he doesn’t mind her being bossy,” said Tomasina.

Linda chuckled. “Wait until she tells him to do something he doesn’t want to do. Then he’ll say no.”

Her comm chimed. It was a message from Maintenance. She opened it, hoping they’d scheduled a repair.

‘Dear Mrs. Schmidt: Thank you for providing additional information. Your repair will be done when a technician is free from higher-priority tasks to attend to it.’

“Lazy bastards,” muttered Linda.

That drew a “Mmmmm?” from Tomasina. Linda explained her problem. She caught her voice rising and controlled it. There were a dozen other Jacks in the park, a mix of parents and retirees. She didn’t want to bother them.

“That’s worrying,” said Tomasina. “I have a dead electrical outlet they haven’t fixed. We have enough working for everything we need, but it’s inconvenient, and . . . is it just a dead outlet or is it part of a bigger problem that we haven’t seen yet?”

“That’s what bothers me, too. On Earth we can have a system collapse and breathe fine while they pick up the pieces. Here . . .”

The two mothers looked around. There were packs of emergency bubbles scattered through the park, enough that no one was ever more than ten meters from one. The children had been trained in how to put one on, but the parents would still be taking action if they heard an alarm or the whistle of an air leak.

“Anyway, I wish I could just find out what priority they’d put on my ticket,” Linda continued.

“You can’t see that?”

“No, the maintenance database is official use only.”

Tomasina’s face went thoughtful. “That sort of system usually doesn’t have sophisticated security. If you’re curious, I might be able to find out for you.”

“I thought you worked information security before Alice came along?”

“I was recruited to security after, ah, working the other side.”

Linda thought about that. “Well, they say you should keep your professional skills in practice for when the kids leave the nest.”

“Good point.”

Two days later they met in the park again. One of the emergency bubble boxes was overgrown by kudzu. Alice set Andy to work tearing away the vines.

Tomasina produced a tablet. “Behold. The maintenance ticket database.”

“Oooh.” Linda leaned in and lowered her voice. “Can you pull up mine?”

A few taps produced the faucet leak repair request. It had her update with the pictures.

“Priority: As time available,” said Linda in a disgusted tone. “That means they might never get to it.”

“Let’s see what the average time to repair for that priority level is.” Tomasina extracted some statistics. “Emergency averages three hours, Critical thirty-two, Serious six days . . . huh. There’s no stats on ‘as time available’ repairs.”

Wrestling with the data eventually disgorged an explanation for the lack. “My God. The last time they completed an ‘as time available’ ticket was twenty-two years ago. They’re just stacking up. Thousands of them. All over the station.”

Linda’s eyes widened. “That’s . . . that’s going to be a disaster. They keep ignoring stuff, someday they’re going to ignore something important. Or some little problems will combine to become a big blowup. And they’ve become used to it.”

“Normalization of deviance.”

The two mothers looked up. They’d ignored the woman on the other side of the path. She had a wrinkled face and grey hair. She’d looked to be napping in the sunlight. Not uncommon for the Jacks who’d used their retirement benefits to stay on the station and save their heart and bones from Earth’s gravity.

“I’m sorry to break in on your conversation, but that’s the technical term. Whenever there’s been a space disaster, it turned out there’s been warning signs but everyone ignored them because they’d gotten away with it before. Then one time several minor problems line up together and—boom.”

Linda shivered. The old woman’s dispassionate explanation brought back memories of documentaries on famous disasters. Sad as news or history—but now Andy was on a station headed toward one of those booms.

“How do you stop it?” Linda asked.

“That’s hard. A new organization can maintain a do it right culture which prevents that, but once they slip into being sloppy they can’t recover without a hard kick from the outside. Usually that’s a technical disaster. Sometimes new leadership can reform things. Or customers can force them to improve, if they’re organized and coordinated. I’m Grace, by the way.”

“Pleased to meet you.” Linda and Tomasina introduced themselves, and named their children, currently making another trip to the compost bin.

“They’re cuties,” said Grace.

“How are we going to give them the kick they need?” asked Linda.

“Step One is always establishing a paper trail.”

Today the children were playing follow the leader. A line of them wound around the poles and through a jungle gym.

Linda, Tomasina, and Grace were a bit farther back from the ring of parents. Linda had a reply from the Chief of Maintenance to their letter. It was terse.

‘Ladies: Thank you for your concern about the Maintenance workload. All of my technicians are fully loaded with high priority repairs. When overtime funding is available, such as for Emergency-priority tickets, they put in extra hours. If your issues become emergencies, or other funding is made available to support overtime work, we will deal with them. Until then, I have to put in some time with a welding torch myself, so please do not bother me with repeats of your request. Have a nice day.’

Tomasina snorted. “I suppose that’s technically polite. He didn’t tell us to go back to cooking for our husbands.”

“It’s very useful,” said Grace. “He’s admitting he doesn’t have the budget or staffing to handle his workload. I thought we’d need several iterations to force that out.”

“I guess our next step is to go talk to his boss. He reports to the Station Administrator.” Linda glanced up from her tablet to check that Andy was still in the line of children.

“The Maintenance budget is public information. Going back to the founding of the station.” Tomasina graphed it on her tablet. “Okay, I’m comparing it to the total population of the station, and the total volume.”

“It’s not keeping up,” said Linda. “No wonder they’re falling behind.”

Grace snorted. “I saw the beginning of that when I was in the Administration. ‘Do more with less.’ ‘Prioritize by severity, not age.’ And laying off the experienced techs to bring in cheaper ones who’d take twice as long to fix something.”

“Tomasina, send me those graphs. We want to put them into the letter to the Administrator.” Linda opened a new file on her tablet.

The reply to that letter took ten days. It wasn’t signed by the Administrator, but by the ‘Assistant Deputy Administrator for Public Affairs.’ Unlike the letter from maintenance, it went on for pages.

“This is bullshit,” said Tomasina as she scrolled through. “Bullshit, more bullshit, even more bullshit.”

“Wait until you get to the end,” said Linda.

“Bullshit . . . ah. ‘Resource allocation decisions are made by the Board of Directors. Funding for the Administration is provided by the stockholders, namely the Government of Ecuador and the sponsoring corporations. Please remember that residence on Artsutanov Station by non-employees is a privilege, not a right. I recommend that you turn your attention to your personal responsibilities.’ That son of a bitch. Is he threatening to evict us?”

Grace had followed along over Tomasina’s shoulder. “Oh, it’s Waverley. Yes, he’s just the sort of weasel who’d make threats like that. I hated him from the moment he arrived, but he was too good at kissing ass for me to get rid of him.”

The kids were playing follow the leader again. The chain of children went by over their heads. Andy had fallen back a few places, unable to keep up with the bigger kids, but he was grabbing vines to pull himself along. Alice was right behind, keeping an eye on her friend.

Linda’s tablet had the Administration organization chart. “Next level up is the Board of Directors. What do you think, start with the Chairman or write all of them at once?”

“Neither. We have a solid paper trail. Now we need to go public.” Grace was grinning.

Tomasina asked, “Dump the maintenance database to the station forums?”

“Ha! Reveal we know restricted data? No. That would get you evicted. And probably us, too, as accomplices. Let’s re-write the Administrator letter as a public statement. I have a ticket for a hatch not sealing I can include as an example. Let’s ask other people to contribute their unfixed tickets, too.”

“We can recycle most of the text. It’ll need a new opening.” Linda started typing.

The first reaction to the public letter came from an unexpected direction.

Linda was serving meatloaf and mashed potatoes with gravy for dinner. It was all sticky enough to stay on their plates. Tony liked it, and Andy was reasonably good about not throwing bits about.

After a bit of chatter about Andy’s learning program, Tony said, “The big boss dropped by my forge today.”

“Oh? New project?” Linda knew the head of the nanoprocessor plant rarely talked to employees at the worker bee level.

“No, personal stuff. Let me try to get his words exact.” Tony’s voice shifted to an imitation of a Texas accent. “‘Someone from Station Administration asked me to lean on you to make your wife behave. I told him to go fuck himself. But figured you oughta know.’ Turns out there’s an open ticket for his apartment, too. Temperature’s stuck.”

“That’s good of him. Um . . . do you want me to behave?”

Tony thought about his answer while snagging an errant chunk of meatloaf and placing it back on Andy’s spoon. “I’m not a fan of picking fights with the big boys. But this isn’t just about the faucet, is it?”

She shook her head. “There’s thousands of open tickets. Most are minor. But there’s cracks that are widening, corrosion that’s spreading, minor problems that become major when they interact. We need them all fixed.”

“Thousands? How do you know that?”

Linda flushed. “I probably shouldn’t have said that. Please don’t tell anyone.”

That kept him silent for a few moments. “This is becoming a big deal. Well, fine. I have some vacation time saved up. Let me know if I need to take time off to watch Andy while you work on . . . this.”

She reached across the table to clasp his hand. “Thank you. He’s not getting in the way, much. And thank you for supporting me.”

Three days later there were still raging forum discussions over the maintenance issues. But less than a hundred people had added their tickets to the list of examples. All of them were as minor as the faucet leak. Ominous to those who cared about ‘normalization of deviance,’ but proof the whole issue was overblown to others.

“I was hoping more people would volunteer their data,” complained Linda.

“A lot of those tickets are obsolete,” said Grace. “People who made a complaint then went back down the elevator.”

Tomasina nodded. “Yep. I found one apartment where eighteen different occupants made the same complaint. Never fixed.”

“Can you pull a list of tickets by people who are still here?” asked Linda.

“The communication directory is public, are they using the same identifiers? Yes. I can do it.”

“Please do. Then let’s split the list and start calling people. We’ll ask them to post their ticket in the forums. How many are there?”

“Subtracting out the ones already posted . . . one thousand, two hundred, and forty-seven.”

“That’s going to be a lot of calls,” said Grace.

Linda wound up making most of the calls. Her partners said they were tired of talking to people after a hundred in a day. Weird.

It took the three of them most of a week to get through the list. The answers broke the list into three parts. Those who didn’t want to be involved. Those who would add their ticket, but didn’t think they’d do anything more. And the ones who wanted to help.

The forum discussions were still going on. The additional tickets were stoking the flames, new ones were posted every hour. The Administration released a statement. It was mostly the same gobbledygook as the reply they’d received from the assistant deputy.

“We should find something for people to do,” said Linda. “We heard all those offers to help, but if we don’t do any follow-up they’re going to lose interest.”

Tomasina cocked her head. “A protest march? Can we do a march in free fall?”

“I wouldn’t recommend it,” advised Grace drily. “A protest sounds good. Pick a volume we can fill. One where people would see us.”

“Filling a place wouldn’t be hard,” said Linda. “We have hundreds of people willing to help.”

Gibson Park seemed full enough with a couple dozen kids and not that many more adults. The station didn’t have many empty spaces. They were hard to keep safe.

“How about the tourist concourse?” asked Tomasina.

Linda grinned. “That’s perfect, all the vendors and tour guides will see us. We’d have plenty of room to spread out.”

“The tourists will see us, too,” said Grace.

“What good does that do us?”

“Some of them are from Ecuador.”

“Right. We want the government to support more Maintenance funding.” Linda began tapping out a list. “We’ll ask everyone to make signs. Should have some suggested slogans for them. Kids can come, they’ll make the protest look bigger.”

The tourist concourse began life as a spacecraft repair hangar. As Artsutanov Station grew, other structures projected past the hangar’s hatch. When it became a hazard for spacecraft to navigate their way in and out, this one was enclosed and a new hangar built to the east end.

Now it held the luxury stores and entertainment venues catering to people rich enough to travel thirty-six thousand kilometers straight up for the fun of it. The center of the volume was still empty. The Jacks performed free fall dances and soccer matches there, events which always brought up extra tourists.

Right now the center just had a wide-meshed net. It provided landing spots for any tourists who managed to lose their grip on the surface and drift through the concourse. They could climb along the net to where it was anchored next to a chicken wrap shop, jewelry store, or some other business, or just wait until one of the guards came out to retrieve them.

The protestors’ children were swarming over the net. They weren’t allowed to play here normally. The under-six kids were paired up with lanyards to keep them from flying off by themselves. The teens were under orders to recover any who went off the net in pairs, or were tangled up.

When the last protestor arrived, Linda gave a shrill whistle. That was the signal for everyone to unfold their signs. She’d told them, “Write big, people will be dozens of meters away.”

Her suggested slogan of ‘FIX THEM ALL’ allowed hand-sized letters to fit on the signs. Grace went with ‘DON’T NORMALIZE DEVIANCE’ which required a smaller font. Many of the protestors had their own slogans, which was a relief for Linda. She didn’t want it to look like they were all just copying each other.

Grace’s suggestion to use her slogan as a chant had been shut down in planning. As people turned to stare at them, Linda led off. “Fix them all!”

More joined in on the chant. “Fix them all!”

The concourse acoustics were terrible—the few musical performers on the station gave up on using it. But the bad resonance made people notice the chant. “Fix them all!”

Some teenagers unfurled a long banner reading ‘1000 TICKETS MUST BE FIXED.’ All the tourists were staring now. “Fix them all!”

The Jacks working the concourse were staring. Or holding up their comms to record the protest. Or putting their comms to their ears to tell someone about it. “Fix them all!”

Linda spotted the streamers. They’d tracked down everyone with significant net presence on the station and told them about the protest. It looked like they were all here, uploading their views of the protest. “Fix them all!”

And here came the guard, crawling up the anchor line for the net. “Fix them all!”

The guard buttonholed the first woman he came to. She pointed toward Linda. “Fix them all!”

He glared. Linda returned a cheerful wave. “Fix them all!”

The guard shouted something totally inaudible under the chanting. “Fix them all!”

He gave up and started crawling toward her along the net. Must be a new hire. A real Jack would have jumped across the gap. “Fix them all!”

When he reached Linda, he shouted, “You can’t do this!”

“Fix them all!”

“We’re allowed to express our opinions,” she retorted.

“Fix them all!”

He kept arguing, trying to convince her to call off the protest. The rest kept chanting. Linda pushed back with arguments for public activity.

“You’re disturbing the peace!” said the guard.

That was the magic phrase Grace had told them to prepare for, the one that meant he was ready to make an arrest. “Fix them all!”

Linda let out another sharp whistle. She followed it with a hand over mouth gesture for silence. Another chorus of “Fix them all” sounded, but at a lower volume. Then it stumbled to an end.

“Thank you for your support, everyone,” announced Linda. “Please go home peacefully. Answer any questions people have. Tell your friends!”

The protestors gathered up their children. They streamed away down the net’s anchor lines, going in every direction.

Tomasina collected Alice and Andy. She’d made it clear she’d rather juggle two toddlers than do the next part.

Linda went down the anchor line closest to where the streamers were filming. They were waiting by the time she reached the wall. She braced for a flood of questions, but they’d decided to take turns while waiting for her.

“Mrs. Schmidt! Could you tell us what your demands are?”

“All we want is for Maintenance to have the resources they need to do their job completely.” The trio had workshopped that as their main sound bite. Hopefully it would bring Maintenance to their side.

As more questions were flung at her, Linda expanded on the needs of the station. There were over a thousand unfixed tickets posted on the forums now, enough to drive home the problem without referencing illegal hacks of the database. She talked about the growth of the station and the lack of growth in Maintenance funding. She even worked in ‘normalization of deviance,’ though not early on.

The youngest streamer asked, “What’s the name of your organization?”

That was a good question. She should have had a good answer prepared. “Homemakers for Fully Funded Maintenance,” Linda blurted.

Hopefully Grace wouldn’t be annoyed by being left out. Maintenance should be happy with it.

The questions started getting trivial, so Linda wrapped it up.

“What will your next protest be?” asked one streamer.

“A surprise,” said Linda, before turning to retrieve Andy.

As she headed toward Tomasina, she passed a bickering pair of tourists.

“You said this place was safe!” shouted the wife.

Her husband said, “It is safe. There hasn’t been a fatal accident on the Beanstalk in over ten years.”

“Then why is everybody saying it’s broken?”

Linda smiled. Their message was getting out.

Tony’s comm chimed during dinner. Not the tone that meant a problem at the foundry. Hopefully it wouldn’t interrupt the meal. He scooped up a spoonful of honeyed peas as he read the message.

Andy tried to suck off the honey and spit out the peas, but Linda saw his expression change and put a hand over his mouth to block that. The boy grudgingly swallowed.

“This looks like an echo from your protest,” he said. “A reminder that all residents must obey Administration policy on pain of fines or eviction.”

“We did comply with the policy,” said Linda. “We went through every line to check what we were allowed to do.”

“It has an updated policy document attached. I’ll forward it to you.”

Tony took over feeding Andy as Linda compared the new policy to the old.

“Whoa. Public gatherings of more than ten people are prohibited without the permission of the Administrator, on penalty of eviction. I don’t think this is legal under the Ecuadoran constitution.” Legally, the station was a ship flying the Ecuadoran flag. “I’m going to have to find a lawyer. Maybe Grace knows one, she has all sorts of connections.”

He caught some high-velocity peas. “Your protest must have really rattled them if they’re pushing back this hard.”

Linda nodded. “Some tourists canceled their stays and went back down. Fewer tourists have been coming up. That’s costing the station thousands of NuDollars.”

“I think they’re bluffing. They can’t evict scores of families. All the businesses would sue for breach of contract.”

“I hope so. Some people do stupid—” She glanced at Andy and picked a different word. “—stuff when their pride is on the line.”

The HFFM held their next planning meeting, as usual, in Gibson Park. Andy and Alice were playing tag.

“It’s time to escalate,” said Grace. “If we’re going to be evicted for just speaking our minds, let’s do something worth being evicted for.”

Linda and Tomasina exchanged looks. Neither one was eager to go downside. And their husbands would be unhappy to lose their jobs.

The older woman glared at them. “Look. This place is on track for a disaster. Sooner or later, boom. If they’re not going to start fixing things, we should get out of here anyway.”

Linda took a deep breath. “You’re right. If it keeps getting worse, I should take Andy back to Earth. What do you suggest?”

“Occupy the Administration offices.”

“How?” burst out Tomasina. “That’s a restricted area.”

“Technically. They don’t lock the doors. And for the ones that are closed, I have some of the passwords.”

The other two stared at Grace. “Just what did you do before you retired?” asked Linda.

That drew a grin. “I was the executive secretary for the chief deputy administrator. For three of them, actually. Everybody I have real dirt on has gone back downside, but I know enough to get us in.”

“Okay. So we go in, chant, keep people from doing their work, until Security takes us away?” Linda was trying to visualize the endgame.

“There’s some tricks we can do to push back against Security. We need to occupy the place until we get our minimum demands met.”

The details of storming the Administration took some planning. Grace produced a map of the offices. “We need to stay clear of Elevator Operations and Fire & Safety. They need to keep running. The rest we mess up. We should totally occupy Accounting, Policy Compliance, and the executive offices.”

Calls to the most enthusiastic of the protestors from the concourse event brought volunteers to do organizing on the day. “We need to send people the right direction and keep them moving. Make sure they get their signs in everybody’s faces and chant the whole time,” Linda told them.

When a debate broke out whether it would be safe to bring the children on this one, Grace ended it. “It’s their lives at risk, too. They deserve to be a part of fighting for a better future. And . . .”

Grace had a truly evil grin sometimes. “There’s some things the kids can do that’ll drive the bureaucrats crazier than we can.”

The Administration offices were next to Tereshkova Park. That park was empty space and grass. No play structures for kids, benches, picnic tables, or anything that might encourage people to hang around. It existed solely to provide a lovely backdrop for the floor to ceiling windows of the Administrator’s office, and nice views for any of his subordinates who were important enough to have a window office.

A youngish bureaucrat with a middle-aged paunch was drifting along the handhold at the side of the park, headed for the main entrance hatch. Linda followed, accelerating as he approached the door.

The bureaucrat held his wristband up to the scanner. The door obediently opened and he pushed off the scanner to float through.

Linda followed close enough she bumped into him. “Oh, excuse me. Thank you for getting the door.”

She slapped her hand on the rim of the door, then pushed off across the lobby.

“Ma’am, you can’t come in here without a badge,” squeaked the bureaucrat.

“Yes, I can,” she chirped. She caught the rim of the door from the lobby to the main corridor, which was standing open as usual.

Administration didn’t have cheap manually closed hatches. They had fancy doors, monitoring air pressure and ready to close if there was a breach or leak. To ensure they didn’t hurt anyone as they closed, a camera watched for anyone passing through.

Linda slapped a piece of tape over the safety camera, just as she’d done to the main entrance. Until somebody noticed that tape, the doors wouldn’t close. And everyone here was distracted. She could hear the receptionist yelling at the line of protestors following her in. She kicked off, headed for the vertical accessway to the executive offices.

The protestors had queued in the corridors surrounding Administration, clutching backpacks and holding their children by the hand. Once Linda went inside, they charged. The children were all told, “We’re going to play Follow the Leader—fast.”

The six woman trained as ‘protest marshals’ were in the lead. They fanned out, headed for their positions. Two would steer people away from the critical operations. The rest would point them toward the offices.

A man with a silk tie clipped to his jumpsuit lost his hold and began spinning in the air as Linda went by, followed by the faster protestors. “What are you doing here?” he yelped.

“Fix them all!” shouted a middle-aged woman.

That startled Silk Tie enough to make him lose his coffee bulb. It spun away, leaking brown drops.

The accessway ended as an opening in the floor of the executive offices area. It looked like they’d tried to copy an Earthside headquarters, down to wood desks and wall paneling. Linda spun in the air until she spotted the door marked ‘Administrator Montvalo.’

There was a grab bar for her to push off of. She went to the Administrator’s office and punched six digits into the pad next to the door.

It opened. Grace was right, they never changed it.

Montvalo was a plump man in his early sixties, a political appointee. His office was focused on a desk which could have been carved from the stump of a sequoia. Rather than float freely, he was belted into a chair to work Earth-style.

The view of Tereshkova Park was lovely.

“What’s the meaning of this?” demanded Montvalo.

Linda gave him a wide grin. “We’re shutting the place down. Just listen.”

She didn’t really need to tell him. The offices were resonating with protestors chanting, children screeching, and bureaucrats complaining. No one without a sound-cancelling headset was going to get any work done here.

“We’ll see about that!” He grabbed his comm.

She didn’t try to stop him. They’d planned for that. She zipped into the accessway, heading back down to the main entrance.

Linda didn’t have to wait long for the Security guards to arrive. There were three of them. That was the normal shift for the tourist areas. They wore black jumpsuits, armored boots and gloves, and equipment belts with stun batons.

“All right, all of you, get out of here!” shouted the older guard. He was handling free fall well. The other two guards were sticking close to their hand holds. They must be new hires.

“We have a right to be here,” began Linda. “Under the Constitution of 2072, we have the right to petition for the redress of our grievances, and are exercising that—”

“You’re trespassing! All of you, get out, or we’ll arrest you. A conviction for trespassing will result in permanent expulsion from Artsuntanov Station.”

As the guard’s speech went on, Linda heard a woman behind her say, “Excuse me, let me through, I have to get through.”

The protestors shouted back, some chanting “Fix them all,” some just hurling abuse. The guard raised his voice over them. “I have the authority to use force to obtain compliance. Our tools use non-lethal voltages, but we are not responsible for any bad reactions—”

A matronly woman pushed her way through the front rank of protestors. “Tommy, don’t you dare!”

The guard froze in shock. “Mom? What are you doing here?”

“I’m trying to get my toilet fixed, Tommy! I have a right to demand this station be in full working order. You should be demanding it, too.”

She pushed forward, shaking a finger in his face as another woman braced her feet. The guard cringed. On Earth, that was a gesture of the head and shoulders, but in free fall his whole body pulled in on itself.

He said, “It’s my duty to restore order—”

“Don’t you dare lay a finger on one of these women! And especially don’t you touch the children!”

The women behind Tommy’s mother were linking arms, forming a chain from pillar to grab bar. Linda glanced around. She spotted Grace hefting her bag. It held a collection of handcuffs, chains, padlocks, and other devices for making it impossible to remove protestors without power tools.

Tommy looked to his fellow guards. Neither of them looked eager to strike women and children. He sighed.

“I bet some tourist has gotten drunk. Why don’t you go arrest him?” suggested his mother.

The guards pulled themselves along the handholds leading the main entrance. The protestors cheered as they left.

Linda hugged Tommy’s mother. “Oh, thank you! That could have been bad.”

“Oh, he was bluffing. I raised him to not hit girls.”

Returning to Montalvo’s office, Linda found him on the comm. Listening to his side of the conversation, he was trying to convince a special forces officer to send a commando squad to deal with the crisis. The officer was needing a lot of convincing.

She went back through the building to make sure things were going as planned. Elevator Operations wasn’t being disturbed, but the watchstanders were coming out on their breaks to see the show. Bureaucrats were breaking down under the stress. Whether they cried or yelled, they were making it uncomfortable for their fellows.

The children were happy. The desks, filing cabinets, and other office furniture made a better environment for hide and seek than any park on the station.

The teens were mostly harassing the bureaucrats. “What games do you have on this thing? Can I play?”

Checking on Montalvo again, he was on the phone with someone else. A private security company, maybe? If he tried to bring someone up from Earth it would take them four days to get here. The occupation would have to succeed before then. They’d brought food and drinks, but not that much.

It was time to escalate again.

Linda moved to the middle of the occupation. A loud whistle shushed the chanting. “It’s snack time for the children! Kids, go up to the executive level for your snacks!”

She led them up the vertical accessway to the wood paneled corridor. Mothers holding sacks followed.

Just having the kids in the executive suite upped the noise level. Some of the Beanstalk-born kids had never touched wooden boards before. They ran their hands over the polished surface, commenting to each other on the texture. The Earth-borns mocked them.

“Line up for snacks!” Each mother on snack duty started passing treats out. Tomasina had organized a raid on the grocery store to buy out everything appropriate. Pudding cups. Already-melting ice cream cones. Sticky toffee. Anything that was gooey. Or could make a mess. Or would leave traces.

Packs of chewing gum were ready for any children who wanted seconds.

In ten minutes the toddlers were a sight. Even the bigger kids had chocolate around their mouths and dirty fingers.

Administrator Montalvo was screaming into his comm to be heard over the babble. “I said four days is too long! You can’t ride the elevator. Rent a rocket! Get here as soon as you can!”

Linda watched the administrator from the door to his office. She looked at the pictures on the wall of Montalvo with famous politicians, the ornately carved desk, the wide picture window. She turned to the crowd. “Hey, kids! Come look at the park! There’s a great view here!”

She ducked through the door and to the side to out of the way of the swarm.

“Oooh! That’s huge,” cried a teenager. More followed after. The room dimmed as children pressed themselves to the window, covering it completely.

“Let me see!” demanded an eight year old. A teen made way for her, leaving ice cream handprints on the window as he bounced away.

Montalvo interrupted his call to try to shoo them away. The children all ignored him. They had a mother’s permission to be here. Some stranger couldn’t overrule that.

Some Beanstalk-born kids focused on the desk. “This is wood, too. Oh, it feels different! Warmer somehow.”

Childrens’ hands slid over the carvings on the sides of the desk. Pudding-smeared fingers brought out the delicate grooving in the wood, highlighting it with chocolate filling.

“Ah! Don’t touch that! Don’t!” Montalvo’s voice was growing shriller.

Linda grinned and crossed her arms. She tucked one foot into a grab bar by the door to hold herself in place. Two other mothers had their comms out to record the Administrator. If he laid a finger on their kids . . .

But the man had enough self-control to not swat any of them. Or he was such a paper-pusher that he couldn’t imagine using anything but words. He turned to face Linda.

She met his eyes. Her grin grew wider.

“Stop them! You have to make them stop!”

“Not until you meet our demands.”

Montalvo was tearing his hair, floating in mid-air, out of control. “What do you want?”

“We want it all fixed. Faucets, drains, outlets, light, every minor repair you’ve ignored for years. Put Maintenance to work on it.”

“I don’t have the money or the people for that!” A toddler bounced off the Administrator’s back, pushing him toward the wall. He seized a grab bar with both hands.

Linda stopped smiling. “Get them. That’s your job. I don’t want to have a disaster because all the little problems added up to a big one.”

“The Board won’t increase my budget. I’ve asked. We’re supposed to be a profit center. They don’t want to invest any more.”

When the HFFM prepared for this protest, they’d decided on some concessions they were willing to make. Linda decided to offer one now, hoping it would soften him enough to reach a compromise. “We’re willing to pay for maintenance. I paid repairmen on Earth, I can pay someone to fix my apartment here. But we’ll pay them for straight time, not overtime.”

“That . . . that might cover more staff. I’d have to do the math.”

Now they were negotiating. Linda let out a whistle. “Kids, time’s up in this room. Back out to the hallway!”

The other mothers herded the children out. Some of the teens helped sheepdog them.

Once the room was clear, Montalvo gave the wall a gentle push and floated slowly back to his desk. Once he’d strapped himself back into the chair, he ran a sad hand over the dirty carvings before turning to his workstation.

Tomasina and Grace floated into the room. They took stations at the corners of the desk. Linda hung off the back of the administrator’s chair, watching his screen.

The first few minutes of discussing numbers were unproductive. Then a grey-bearded man floated into the room. “Did you need me, sir? Oh, hello, Grace.”

“Albert. Good to see you’re still working.”

The man’s eyes flicked from Grace to the other women, then the evidence of children smeared on window and desk, then back to Grace. “Part-time. But I’m staying useful. I see you are, too.”

Grace just smiled in response to that.

The administrator cut short the amenities by demanding help with the maintenance budget. Albert added the revenue from tenant repairs, with several projections depending on how many more maintenance personnel were added. “Twelve full time technicians seem the optimum, sir.”

“What a coincidence,” said Montalvo sourly. He pulled up his message archive and began a reply.

Linda watched over his shoulder.

‘To Chief of Maintenance. Your staffing request of 20th last is approved, effective immediately. Please hire the necessary personnel as soon as possible. Funding will be provided on a task basis, see follow-up message. Signed, Montalvo, Administrator.’

After a glance at the people hovering around him, he grudgingly added them to the address list for the message.

“I’ll send the payment arrangements we discussed out within the hour,” promised Albert.

Montalvo pressed send. “Satisfied?”

“Yes, thank you,” said Linda. “I’ll sleep better knowing the station is not going to fall apart on us.”

“Then get those brats out of here!” he bellowed.

“Gladly, sir,” said Linda.

Grace held up her comm. “I notified the bakery, they’re delivering them now.”

Linda went through the doorway. “Kids! There’s cake in the park. Everybody go to the park, we’re having cake to celebrate!”

The plumber was only half an hour late for his appointment. He introduced himself as Jesus, “And this is Esteban, he’s new, he’s watching while he learns his way around.”

The apprentice hooked a foot and both hands onto grab bars.

Jesus looked at the blob hanging from the faucet. “Oh, you’ve got one of those, ma’am. Easy fix.”

Linda held tightly onto Andy. He wanted to play with the strangers, and their power tools.

Jesus pulled out a tablet. “First thing we do is turn off water supply. That takes three valves to isolate this section.” He showed the interface to the apprentice. “Once that’s done, we can take it apart.”

Two different wrenches were needed to disassemble the faucet assembly. Andy watched as if hypnotized.

“Yep, thought so. Subcontractor for this section ran small batches of seals, and last one in each batch was incomplete. I printed up a new one before I came over.” The plastic part went in for the bad one. In minutes the faucet was intact again.

“Now let’s turn the supply on and see if that fixed it.” A quick squirt of water filled one of Andy’s sippy cups. They watched the faucet as the boy drank, but no bubble of water appeared by the time he finished it.

“I think that’s got it. That’ll be thirty NuDollars, ma’am.”

A few strokes on her tablet settled Linda’s bill. “Thank you very much, Jesus.”

“Thank you, ma’am. It’s nice to look forward to not having overtime every day.”

If you’d like to read this story and others on paper, I have two story collections available as paperback and hardcover. Ultimate Conclusions has stories and gaming articles I’ve published in other anthologies and magazines. Unmitigated Acts collects the first seventeen stories from this Substack. Here’s the cover of the second collection:

Thank you, that was a unique, interesting, and entertaining story!